The epidemic has exposed the tension between “old Samoa” ways and the power of new technology to spread misinformation.

When “PJ” Faumuina grew up in Samoa, vaccination was not even a question.

“There was no discussion. It was, ‘The programme is coming to school today, all line up and get your vaccinations.’”

Families, he said, followed leaders – whether from the family, village, church or district – who made decisions on behalf of their communities. If they decided that children should be vaccinated, it happened.

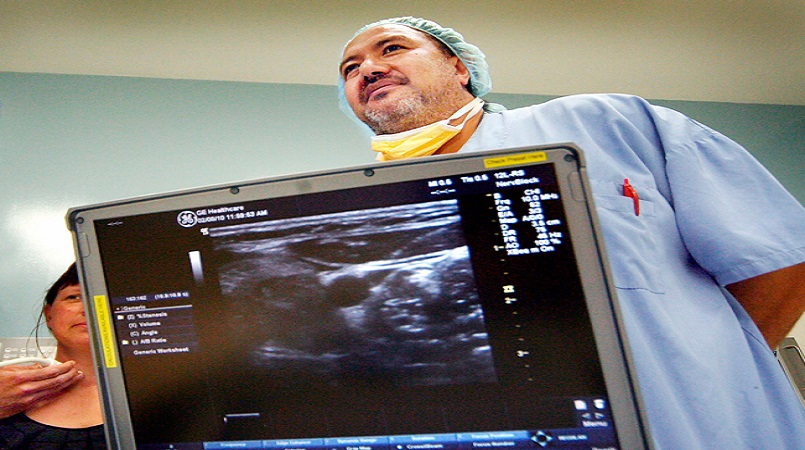

Faumuina, 57, who holds the matai title of Faumuina from Samoa’s Sagaloa district and who is now an ear, nose and throat surgeon with Whanganui District Health Board, thinks his native country is caught between those “old Samoa” ways of decision-making, which may appear autocratic to outsiders, and Western ways that emphasise democracy and individual rights.

The authority to make some decisions has slipped through the gap, he thinks. Public-health messages and vaccination rates seem to be among the casualties.

Semisi Aiono, a general surgeon also with Whanganui District Health Board, thinks the problem is at least partially about the lure of new technology and the misinformation that it disseminates. Sometimes it has a higher status than the authorities on whom people traditionally relied for information.

“I don’t see it so much as a clash between the old ways and the new ways, rather as a change in the way people receive information and a change in what they trust,” Aiono tells the Listener.

Younger generations feel they hold the key to making decisions, he thinks. “They may feel they are better informed because they have mobile phones.” Instead, he thinks, they are more vulnerable to misinformation and, in a small society, it can be disseminated widely and quickly.

Samoa’s population is approaching 200,000 – similar to Hamilton – mostly living in villages and rural areas on the two main islands, Savai‘i and Upolu.

Samoa moved from “Least Developed Country” to “Developing” status under United Nations criteria six years ago, but struggles with high levels of public debt and poverty. It depends on remittances from Samoans overseas – particularly in New Zealand and Australia – and is at high risk of natural disasters.

All social systems are complex, so, inevitably, more than one factor will have contributed to Samoa’s vulnerability to the measles epidemic that has claimed 83 lives.

Aiono says he felt “a niggle” when it was first reported in 2018 that two babies had died after a botched attempt to vaccinate them.

That incident appeared to damage people’s faith in the health system and, in retrospect, would have been a good time for a targeted education campaign.

“We are so good at learning afterwards,” he says.

The toll of the epidemic has left people afraid, but also much more aware and willing to accept new health decrees.

“In that way it has helped the authority of the public health system and it has raised awareness but, gosh, what a terrible cost to have to pay with children’s lives instead of learning beforehand.”

n regular visits to Samoa to help relieve medical colleagues’ workloads, Aiono has struggled to find a way to get a podcast aired or a community radio outlet where public health can be talked about.

If he could, the messages he would convey would be simple, he says, such as addressing domestic violence. “These are destructive paths and habits that families have modelled for younger generations to follow. How do you break those cycles?

“Healthier diet is another very big topic. We’re seeing a slow epidemic of strokes, diabetes, heart disease and kidney failure because of dietary and lifestyle changes and we need education about that.

“People need to be empowered to buy and grow vegetables. People will now value fast food or white bread rather than vegetables.

“The irony is that I can see the problems that Samoa is facing as a microcosm of what we in New Zealand are facing, and in a way, it’s a warning to us that this can so easily happen and get out of control.

“An epidemic can be slow, creeping and insidious. Over years, you see the number of people with diabetes requiring amputations and, if you collected them all in one place, you’d see how much suffering it’s caused. Instead, we can routinise disasters when they happen drip, drip, drip.”

Faumuina thinks the wake of the measles disaster will bring change. During the epidemic, the Prime Minister, Tuilaepa Sailele Malielegaoi, effectively ordered a complete shut down of society to prevent the disease spreading.

“I remember saying to some of my colleagues that there are not many countries where the leader can come out and – putting aside whether he was right or wrong – say in a draconian way, ‘This is what’s going to happen.’” And people obeyed.

To Faumuina, it was “old Samoa” again: forget modern democratic concepts and political correctness and do what needs to be done. The same tension between old and new ways may be evident in reviewing the epidemic, he thinks.

“The old attitudes will be that it’s happened, 83 people have died and nothing we do will bring them back, so, do we get our machetes out and go looking for some other heads to cut off? No. We are Samoan, let’s just be forgiving. When we’re really cheated, we’re heated, but we don’t need to be heated now. It’s over, it’s done, let’s learn from it and move on.

“Then there are those with a very Western sense of accountability, who say that because there were systems in place and job descriptions and frameworks to be accountable to, let’s find out what those frameworks were and who was supposed to be accountable, and let’s bring those people to justice.”

Faumuina does not know which way it will go, but will keenly watch.

“There will be a significant shake-up. I don’t think we’ve seen the end of it.”