Many in the Saposa Islands are wrestling with the dilemma of starting a new life on the mainland or staying to watch their homes vanish.

- An impossible choice: leave your island or fight to stay? – podcast

- In Samoa we are born into land, climate change threatens to take it away from us

- An impossible choice: when climate change arrives at your door – podcast

by Kalolaine Fainu in the Saposa Islands, Papua New Guinea.

Francis Tony is buried on an island that is shrinking.

The sea breaks on a shoreline that is now less than five metres away from his simple gravesite on Toruar Island in the Solomon Sea. But his son Christopher Sese says the family have no plans to move Tony’s bones to a new gravesite.

“My father will be like the captain of the Titanic. When Toruar Island goes down, he will go down with it,” he says.

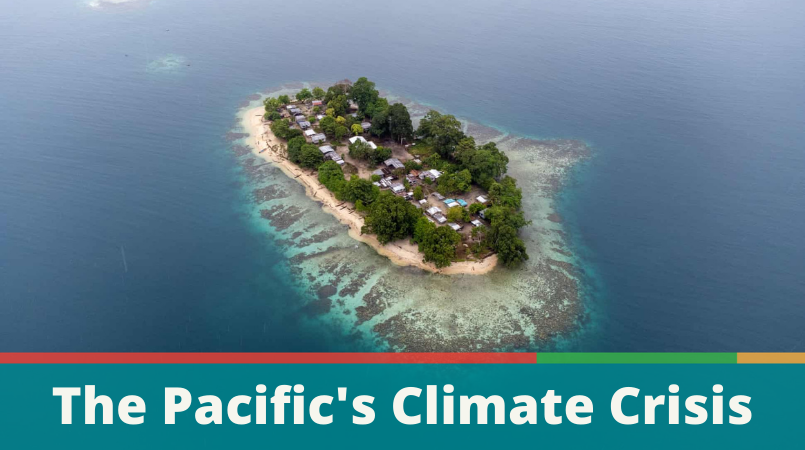

The sea is closing in on Toruar Island. Photograph: Kalolaine Fainu/The Guardian

Toruar lies in the Saposa Islands group, south of Bougainville, in the east of Papua New Guinea.

While the nearby Carteret Islands drew international attention a decade ago, with some saying residents had become the first climate refugees, there are a number of island groups around Papua New Guinea that are disappearing or becoming uninhabitable due to rising sea levels.

Paramount chief John Wesley, of Torotsian Island in the Saposas, points at a grassy area in front of the school building, explaining that during king tides the entire field is covered in water.

“Last time, the boats from town drove all the way in and were spinning around on top of the school field,” he says.

Paramount chief John Wesley says his community needs support. Photograph: Kalolaine Fainu/The Guardian

In addition to being paramount chief, Wesley is a civil engineer. He has been trying his best to get the community involved in small projects around the island, such as building a seawall from old 10kg rice bags filled with dead coral and shells to protect the land from rising waters. He has also put together proposals to get support from local, national and international bodies in an effort to secure land protection measurements.

But he fears a move may be inevitable.

“The big challenge is our children, our future generations. I think if we decide to move to the mainland now, maybe our future would be much better.”

Local school teacher Arani Kaitov was born and raised on Torotsian island and says she talks to her students about natural hazards and the impact climate change is having on their island home.

“I usually tell the kids that because the seas are wearing away the soil and our land is getting smaller, and because the population is growing, that in the future we’ll move to the mainland.”

Schoolteacher Arani Kaitov on Torotsian island. Photograph: Kalolaine Fainu/The Guardian

‘Now, we can’t plant anything’

Sea levels in the western Pacific Ocean have been increasing at a rate two to three times the global average, meaning there has been net rise of 0.3 metres in the last 30 years.

The most obvious impacts of rising sea levels are coastal erosion and flooding of low-lying land. But communities are affected long before their islands become submerged. Saltwater seeps into groundwater, making it unfit for household use and leaving communities dependent on rainwater for drinking, and meaning communities cannot grow crops.

Bobby Soma was born on Toruar in 1962 and says he has noticed a huge change in both the environment around the island and the standard of living for the people in his community in his lifetime.

“Before we could plant bananas, there were some coconut trees and some breadfruit,” he says. “We even had mangoes. But now, we can’t plant anything here because the soil is no longer fertile, it is just sand.”

Soma says there is no hope that the people on Toruar can remain and be self-sufficient. Even now the islanders must rely on garden produce from the mainland to supplement their diets.

Soma relocated to the mainland in 2014 but has made a special trip back to Toruar to show the impacts of the rising sea.

Bobby Soma inspects the rotting foundations of a house he built on Toruar that was once 15 metres from the sea. Photograph: Kalolaine Fainu/The Guardian

“It’s hard for us to move to the mainland,” he says. “Because [Toruar] is where our mothers lived and where they gave birth to us. It’s hard for our new generation to move.”

Soma moved to the mainland to show his people that a new life was possible, despite the emotional challenges that come with leaving their birthplace.

And there are some advantages; he is now able to grow his own food again.

“On the island we had to spend money everyday just for food, cocoa or whatever, but on the mainland there is plenty of land, so I’m happy because it is a new start for me.”

Soma says developed countries should do more to support small islands like Bougainville and work with local governments to provide assistance to those, like him and his Saposa community, who will have no choice soon but to find new land to relocate to.

“Many big industries in the big countries are making big projects and developing their country, but they are just making things hard for us.”

‘The island will be gone’

For the past 12 years, Ursula Rakova has been helping relocate members of her community from the Carteret Islands, about 80km north-east of Bougainville, to the mainland.

The remote circular atoll sits perched on top of a reef. Rakova estimates its highest elevation is only 1.2 metres above sea level.

Ursula Rakova, executive director of NGO Tulele Peisa, on Bougainville. Photograph: Kalolaine Fainu/The Guardian

“It’s very, very low. If you put all the islands together, five or six islands … they are very small, you basically can walk around the islands in less than an hour.”

It is the tiny footprint of land left on the Carteret Islands that makes life there unsustainable.

“Maybe the islands will remain, and maybe there will be trees, but in terms of sustaining our lives and feeding ourselves, that time has gone,” she says.

Responding to a call from elders in her community who were desperate for a solution, Rakova set up a local NGO called Tulele Peisa which translates to “sailing in the wind on our own” and which has been instrumental in relocating families from the Carteret Islands to the mainland.

Ten families have now successfully been relocated to the village of Tinputz, with which her NGO built a relationship, and have made new homes on land provided to them by the Catholic mission.

“Families are given a house, a water tank and one hectare of land where they can grow cocoa, coconut and also garden food. We have food crops like sweet potato, cassava, tapioca, bananas, greens and there are many other vegetables that we can grow,” she says.

Although leaving their island home can come with challenges, Rakova says the standard of living for the families living in Tinputz has gone up hugely, as the new location provides them not only with fertile land to grow food to eat, but the cocoa blocks provide a means of earning an income.

Morris Carmen and his family were among the first to sign up for the relocation to Tinputz and agrees that the standard of living is much better on the mainland.

Morris Carmen, the first person to relocate from the sinking Cateret Islands to Tinputz. Photograph: Kalolaine Fainu/The Guardian

“I have a block of land with 300 cocoa trees and coconuts that I’ve planted too. I harvest about two bags from these trees and go and sell them. The little money that I get from this goes to my children’s school fees and medical expenses. When they’re sick I give them a little bit of money so that they can go to the hospital.”

Carmen says that he has left behind many friends and family members, all of whom he hasn’t seen since he left over 10 years ago, but his motivation for relocating was for the benefit of his children and their future.

“There won’t be any [island in the future] from what I see. The island will be gone, the sea will destroy the island. There are plenty of people too, where will they live? It’s hard to live there.”

Story first published on The Guardian